ARPS: From a Concrete Idea to Champagne

This article was published in the RPS Benelux eJournal (Vol. 12, Autumn 2018) and on the RPS blog on June 4, 2019.

Becoming a better photographer is a life-long learning process. It requires study, practice, feedback and recognition. You need to study the technique and the masters. Practice as many different things as possible. This need not be a solitary endeavour, because the Royal Photographic Society (RPS) provides for feedback with their study groups and for recognition with their distinctions.

Where to Start?

I've been a member of the RPS Benelux for about a year, after joining a couple of events and some study group meetings, organised and guided by Janet Haines ARPS. At those meetings, I got in touch with the concepts of distinctions and panels. Distinctions are rewards that one can receive in three different levels: L(icentiate), A(ssociate) and F(ellow). They are rewarded depending on a submitted panel. Depending on the level one needs to fulfill certain requirements. For L, 10 pictures demonstrating various techniques are required. The layout of the pictures in a panel is quite important. The L panel is where one would usually start. However, I was hesitating between going for a Licentiate panel (demonstrating diversity and technique) and an Associate panel (demonstrating style and story). I had followed many courses and practised many techniques and subjects before joining the RPS. What I felt lacking in my photography was not so much technique, but content. My goal is still to develop a more coherent and meaningful body of work, which consists of themes, series and stories. This is exactly what the Associate distinction is all about. So, finally, I gave it a try and took a series of pictures to our study group meeting. One of my favourite themes is architecture. The first feedback was a disaster: some good pictures, but no story, no theme, and no apparent intention - I missed everything that I was trying to achieve! Incidentally, I was following a course by David DuChemin, which is all about intent (The Compelling Frame). Finally, I also understood the concept of the Statement of Intent (SoI) that is required for the A level. You have to start with the SoI! Taking pictures comes second. And - very different from the L level - you have to demonstrate a consistent style. Well, that's the theory and good practice, but some people were successful with writing the SoI after the fact... Nevertheless, I found it very helpful and inspiring to go shooting with a concept and style in mind. It can help to look for views that otherwise might appear less interesting.

Brutalism

So, I knew that I wanted to do "something" with architecture and cityscapes. I also had a theory in mind that I wanted to translate into pictures for decades, but never managed before. This was the time to go for it. This theory is formulated in the book "The Savage Mind" by the French philosopher Claude Lévi-Strauss. It was cited in the well-known book "Collage City" about (post-)modern urbanism by Colin Rowe. A specific passage in Lévi-Strauss deals with the relationship between structure and events. Structure refers to the intentionally designed and built, while the events refer to the unplanned and unexpected things that happen spontaneously. It is the interaction between these two concepts that creates exciting environments. But how could one visualise such an abstract and generic concept?

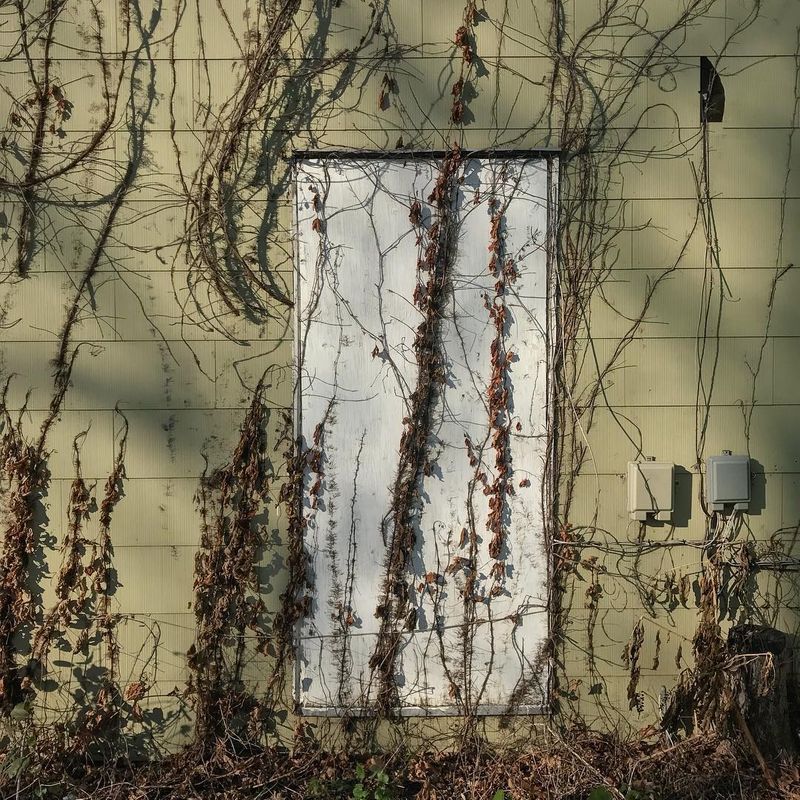

Another inspiration came from a picture by Stephen Shore that I saw accidentally on Instagram: an industrial facade with plants growing all over. Now, I had a concrete idea! I would use the example of Brutalist architecture for my purpose. The term "brutalism" is wrongly translated - it refers to the French term "béton brut" as Le Corbusier used it - raw concrete (no brutality involved). The use of raw concrete is interesting in at least two aspects: the raw nature of the material invites environmental change, and the material can be shaped in any imaginable way, which often results in rather organic constructions. Thus, the relationship between the planned ideal and accidental modifications would become apparent in more than one way, as intended. In terms of style, I wanted to step beyond the obvious. Again, inspired by David DuChemin, I went from colour to black & white and from 3 by 2 to square format. This new way of composing liberated my pictures. Restricting myself to this style allowed me, at the same time, to see the subjects in a new light. In combination with the post-processing, this style fits very well with the theme: Naturally Concrete.

Working on the Idea

A month after my poorly received first presentation of random architectural pictures at the study group, I came back with a statement of intent (see below) and a new set of pictures. This time, the feedback was much more positive. My new panel was intended simply as an example of what I was trying to do, but it was far closer to a potential A panel submission than anything I had ever produced before. Apparently, I was on the right track. It was now or never and the idea of an L panel was definitely left behind.

Shortly after the study group meeting, an advisory day was planned in Ghent. The motivation to present a good panel there was very high. It proved to be a very interesting and inspiring weekend. Besides learning a lot from other panels, the feedback on my panel by Ray Spence FRPS, head of distinctions, was encouraging. I also learned about the different categories, or genres, and their different rules. It appeared that my panel would either fit in the Conceptual or Fine Art category. With Conceptual, the story is paramount and the SoI can be extended to explain it in more detail. With Fine Art, the quality of the pictures is what counts most. After some hesitation, I decided to go for the Conceptual category, because I felt that my panel had an important story to tell.

Submission

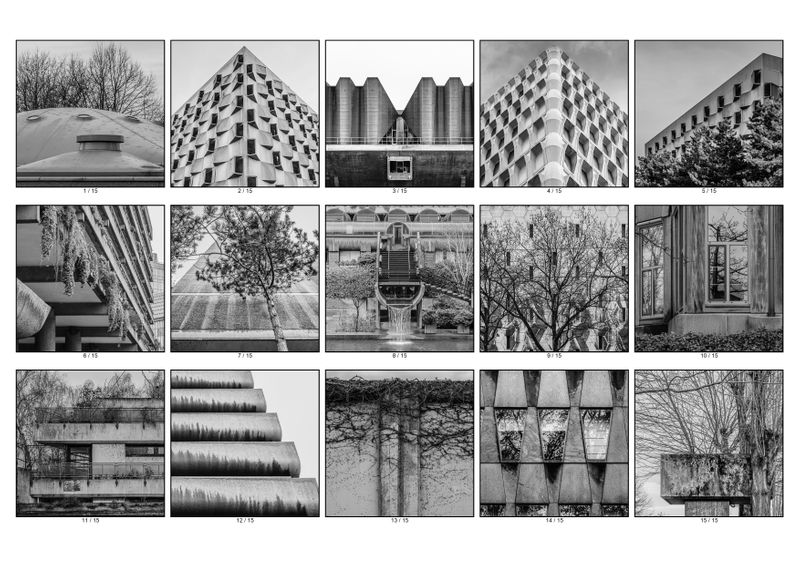

More pictures were made and the selection of the best ones only became more difficult. Not only does one have to select perfect pictures, but they also have to fit in the panel and complement each other. The SoI was fine-tuned in many iterations. This process is the hardest part and the one which benefits the most from discussions in the study group. After selecting, printing and framing the pictures they had to be sent to Bath, just in time for the next assessment day. The panel was accepted and I received confirmation a few days later [5]. A bottle of Champagne was ready to be opened for the occasion!

Although the ideas and intentions were ripening for decades, the period from the first idea for a panel to a concrete result in terms of a submission was rather short. It took less than half a year from conception to award. Sometimes, it can take ages before you're ready, but there's nothing to stop you when you are.

The support that I got from the study group and my wife and children was extremely important. The best way to learn is to try and get feedback. And, for me, learning and improving myself and my photography are extremely important. I have learned a lot in this process and become a better photographer. Now, I'm ready for new challenges, again. Never stop learning...

STATEMENT OF INTENT

Naturally Concrete

We make the world that we live in—at least, that's what we believe. We create structures that organise our lives. We construct the buildings that we inhabit. Yet, not everything happens as planned. Our structures are subject to unpredictable events that modify them. The wrongly-named Brutalist architecture plays with the concepts of the raw matter and accidental events, as well as their juxtapositions and relations to organised structures (according to Lévi-Strauss [1]). The use of raw concrete enables free-form buildings that sometimes assume organic textures, patterns and shapes. Moreover, age and environmental conditions leave marks on the concrete buildings and assimilate metamorphosis. Raw concrete invites the symbiosis between built structures and events in nature.

It is my intention to show the beauty and unexpected harmony between human-built structures and natural mutation.

[1] Claude Lévi-Strauss, La Pensée Sauvage, Librairie Plon, Paris, 1962HANGING PLAN

Naturally Concrete